A new TV series called Britannia takes as its setting the Claudian invasion of Britain in 43 CE which began almost 400 years of Roman occupation of England and Wales. In the community at large, the main talking point seems to be whether or not Britannia is trying to be another Game of Thrones clone. In the Druid community, the major topic of debate is the show’s portrayal of Druids. In weighing into these discussions, I am at the considerable disadvantage of being unable to see the programme in question due to not being a subscriber to Sky. That said, I’ll have a go based on what little I’ve been able to glean from brief clips online and other people’s comments.

A new TV series called Britannia takes as its setting the Claudian invasion of Britain in 43 CE which began almost 400 years of Roman occupation of England and Wales. In the community at large, the main talking point seems to be whether or not Britannia is trying to be another Game of Thrones clone. In the Druid community, the major topic of debate is the show’s portrayal of Druids. In weighing into these discussions, I am at the considerable disadvantage of being unable to see the programme in question due to not being a subscriber to Sky. That said, I’ll have a go based on what little I’ve been able to glean from brief clips online and other people’s comments.

The chief Druid in the series is portrayed by Mackenzie Crook (above), most recently gracing our screens in the excellent BBC series, Detectorists. In Britannia, he is heavily made up and seems to portray his character as something between a circus performer and a homicidal maniac. Some modern Druids have been quoted in the press as being deeply offended by this portrayal on the grounds that modern Druids are peace-loving people who honour the cycles of nature. In most cases, this is undoubtedly true. I’m a life-long pacifist myself. We may, however, legitimately ask whether the same was true of Druids two thousand years ago. Classical Druids’ ability to bring peace to warring factions is evidenced in Diodorus Siculus’ 1st century BCE statement that, “Often when the combatants are ranged face to face, and swords are drawn and spears bristling, these men come between the armies and stay the battle, just as wild beasts are sometimes held spellbound. Thus even among the most savage barbarians anger yields to wisdom, and Mars is shamed before the Muses.”

The chief Druid in the series is portrayed by Mackenzie Crook (above), most recently gracing our screens in the excellent BBC series, Detectorists. In Britannia, he is heavily made up and seems to portray his character as something between a circus performer and a homicidal maniac. Some modern Druids have been quoted in the press as being deeply offended by this portrayal on the grounds that modern Druids are peace-loving people who honour the cycles of nature. In most cases, this is undoubtedly true. I’m a life-long pacifist myself. We may, however, legitimately ask whether the same was true of Druids two thousand years ago. Classical Druids’ ability to bring peace to warring factions is evidenced in Diodorus Siculus’ 1st century BCE statement that, “Often when the combatants are ranged face to face, and swords are drawn and spears bristling, these men come between the armies and stay the battle, just as wild beasts are sometimes held spellbound. Thus even among the most savage barbarians anger yields to wisdom, and Mars is shamed before the Muses.”

On the other hand, classical Druids  relied for their livelihood on the patronage of the warrior caste that formed the upper echelons of Celtic society, while some Celtic sacred sites were decorated with human skulls (right) or piled with the bones of the dead. Then there are the Druids in medieval Irish literature who use battle magic against their enemies, hurling balls of fire or causing rocks to rain down from the heavens. There is also evidence for human sacrifice among the Celts, albeit on nothing like the industrial scale suggested by their Roman conquerors. Need these have involved Druids?

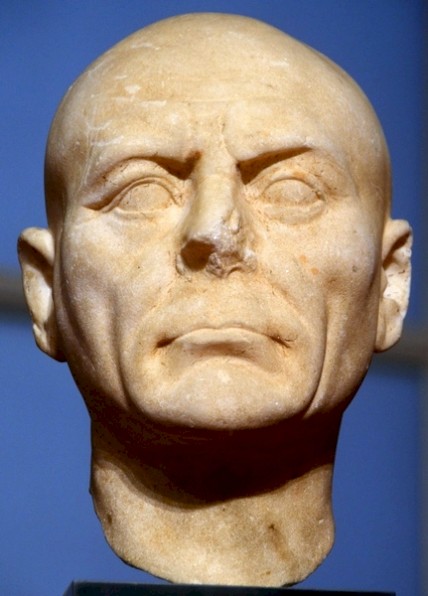

relied for their livelihood on the patronage of the warrior caste that formed the upper echelons of Celtic society, while some Celtic sacred sites were decorated with human skulls (right) or piled with the bones of the dead. Then there are the Druids in medieval Irish literature who use battle magic against their enemies, hurling balls of fire or causing rocks to rain down from the heavens. There is also evidence for human sacrifice among the Celts, albeit on nothing like the industrial scale suggested by their Roman conquerors. Need these have involved Druids?  Diodorus Siculus (left) suggests that they did, writing that the Celts “have philosophers and theologians who are held in much honour and are called Druids. It is a custom of the Gauls that no one performs a sacrifice without the assistance of a philosopher, for they say that offerings to the gods ought only to be made through the mediation of these men, who are learned in the divine nature and, so to speak, familiar with it, and it is through their agency that the blessings of the gods should properly be sought.”

Diodorus Siculus (left) suggests that they did, writing that the Celts “have philosophers and theologians who are held in much honour and are called Druids. It is a custom of the Gauls that no one performs a sacrifice without the assistance of a philosopher, for they say that offerings to the gods ought only to be made through the mediation of these men, who are learned in the divine nature and, so to speak, familiar with it, and it is through their agency that the blessings of the gods should properly be sought.”

Even from this fragmentary and at times dubious evidence, it seems likely that classical Druids were considerably more robust in their approach to life and death than many contemporary Druids are willing to believe.

The makers of Britannia, however, clearly take Roman descriptions of Druids as the basis for their portrayal. This is problematic in that the Romans were intent on conquering the Celts and as part of that agenda they needed to demonise their intellectual caste, the Druids, since they represented the only organisation in Celtic society capable of uniting warring tribes to resist Roman plans for conquest. To this end, Roman writers characterised Druids as the most bloodthirsty members of a savage race, accusing them of all manner of barbarity, including nailing people’s entrails to trees and making them run around them, divining the future from their death throes. Greek writers, by contrast, who were well acquainted with the Celts, described Druids as wise philosophers, eloquent speakers and counsellors to kings. From what I can gather, Britannia over-emphasises the brutality of Druids for dramatic effect while downplaying the other activities for which Druids were noted, like storytelling, genealogy, healing, music, poetry and the aforementioned counselling.

It seems that the Druids in Britannia are also portrayed as regular drug users. There is absolutely no evidence for this. On the contrary, I suspect that the inhabitants of 1st century CE Britain would have felt much that same as the more recent inhabitants of Siberia, i.e. that any Druid or shaman who needed drugs to access the Otherworld was pretty lousy at their job.

It seems that the Druids in Britannia are also portrayed as regular drug users. There is absolutely no evidence for this. On the contrary, I suspect that the inhabitants of 1st century CE Britain would have felt much that same as the more recent inhabitants of Siberia, i.e. that any Druid or shaman who needed drugs to access the Otherworld was pretty lousy at their job.

On the whole, then, it looks as though the portrayal of Druids in Britannia revels in dope and gore to excess and ignores most of the other priestly functions Druids fulfilled in their communities. This should go down well in America, where, for historical reasons, the Roman view of Druids as barbaric monsters has always been prevalent.

Incidentally, I note that Britannia Druids are shown gathering in a sort of two storey Stonehenge (above). This will doubtless revive the old argument about Druids being a Celtic priesthood and the Celts not arriving in Britain until many centuries after such megalithic monuments were abandoned. Here again, all may not be as it seems. Julius Caesar, one of the few classical writers who actually met Druids, was told by them that the Druid faith originated in Britain (Gallic Wars, bk.6, ch.13). Celtic culture, on the other hand, originated in central Europe. Assuming Caesar’s informants were accurately reporting their tradition and that Caesar accurately passed on their words, this means that Druids were not Celtic in origin, but native to Britain before Celtic culture arrived here. In which case, as many reputable archaeologists have argued, it is possible that Druids were directly descended from those who built and used Stonehenge and other monuments. There were Iron Age shrines in southern Britain which, like many of their megalithic predecessors, consisted of timber circles enclosed by earthwork banks and ditches, arguing for some continuity of tradition. Iron Age and Romano-British finds at megalithic sites such as the Medway tomb-shrines show that they continued to be visited, though for what reasons we can only speculate. The Iron Age hill fort known as Vespasian's Camp lies a little over a mile from Stonehenge, a short stroll away and Iron Age and Romano-British pottery and other artefacts have been found within the henge. It seems impossible to believe that Druids would not re-use at least some of the stone circles built by their, and our, ancestors. It is hard to imagine that they would not have felt the same sense of ancestral connection and simple wonder that we ourselves feel when we visit such places, even harder to believe that they would simply ignore them.

Incidentally, I note that Britannia Druids are shown gathering in a sort of two storey Stonehenge (above). This will doubtless revive the old argument about Druids being a Celtic priesthood and the Celts not arriving in Britain until many centuries after such megalithic monuments were abandoned. Here again, all may not be as it seems. Julius Caesar, one of the few classical writers who actually met Druids, was told by them that the Druid faith originated in Britain (Gallic Wars, bk.6, ch.13). Celtic culture, on the other hand, originated in central Europe. Assuming Caesar’s informants were accurately reporting their tradition and that Caesar accurately passed on their words, this means that Druids were not Celtic in origin, but native to Britain before Celtic culture arrived here. In which case, as many reputable archaeologists have argued, it is possible that Druids were directly descended from those who built and used Stonehenge and other monuments. There were Iron Age shrines in southern Britain which, like many of their megalithic predecessors, consisted of timber circles enclosed by earthwork banks and ditches, arguing for some continuity of tradition. Iron Age and Romano-British finds at megalithic sites such as the Medway tomb-shrines show that they continued to be visited, though for what reasons we can only speculate. The Iron Age hill fort known as Vespasian's Camp lies a little over a mile from Stonehenge, a short stroll away and Iron Age and Romano-British pottery and other artefacts have been found within the henge. It seems impossible to believe that Druids would not re-use at least some of the stone circles built by their, and our, ancestors. It is hard to imagine that they would not have felt the same sense of ancestral connection and simple wonder that we ourselves feel when we visit such places, even harder to believe that they would simply ignore them.

I’ll probably watch Britannia when it comes out on dvd. After all, when Emma Restall Orr and I (left) sat on a bench watching the rough, grey winter sea at Eastbourne way back in the 1990s, discussing the future direction of the British Druid Order, we decided to make it our goal to bring sex, fear and death back into Druidry. In Britannia, we may have found an ally. In any case, a show that uses Donovan’s ‘Hurdy Gurdy Man’ as a theme tune can’t be all bad…

I’ll probably watch Britannia when it comes out on dvd. After all, when Emma Restall Orr and I (left) sat on a bench watching the rough, grey winter sea at Eastbourne way back in the 1990s, discussing the future direction of the British Druid Order, we decided to make it our goal to bring sex, fear and death back into Druidry. In Britannia, we may have found an ally. In any case, a show that uses Donovan’s ‘Hurdy Gurdy Man’ as a theme tune can’t be all bad…

“Histories of ages past,

unenlightened shadows cast

down through all eternity

the crying of humanity.

‘Twas then when a hurdy gurdy man

come singing songs of love….”

Peace’n’love,

Greywolf /|\